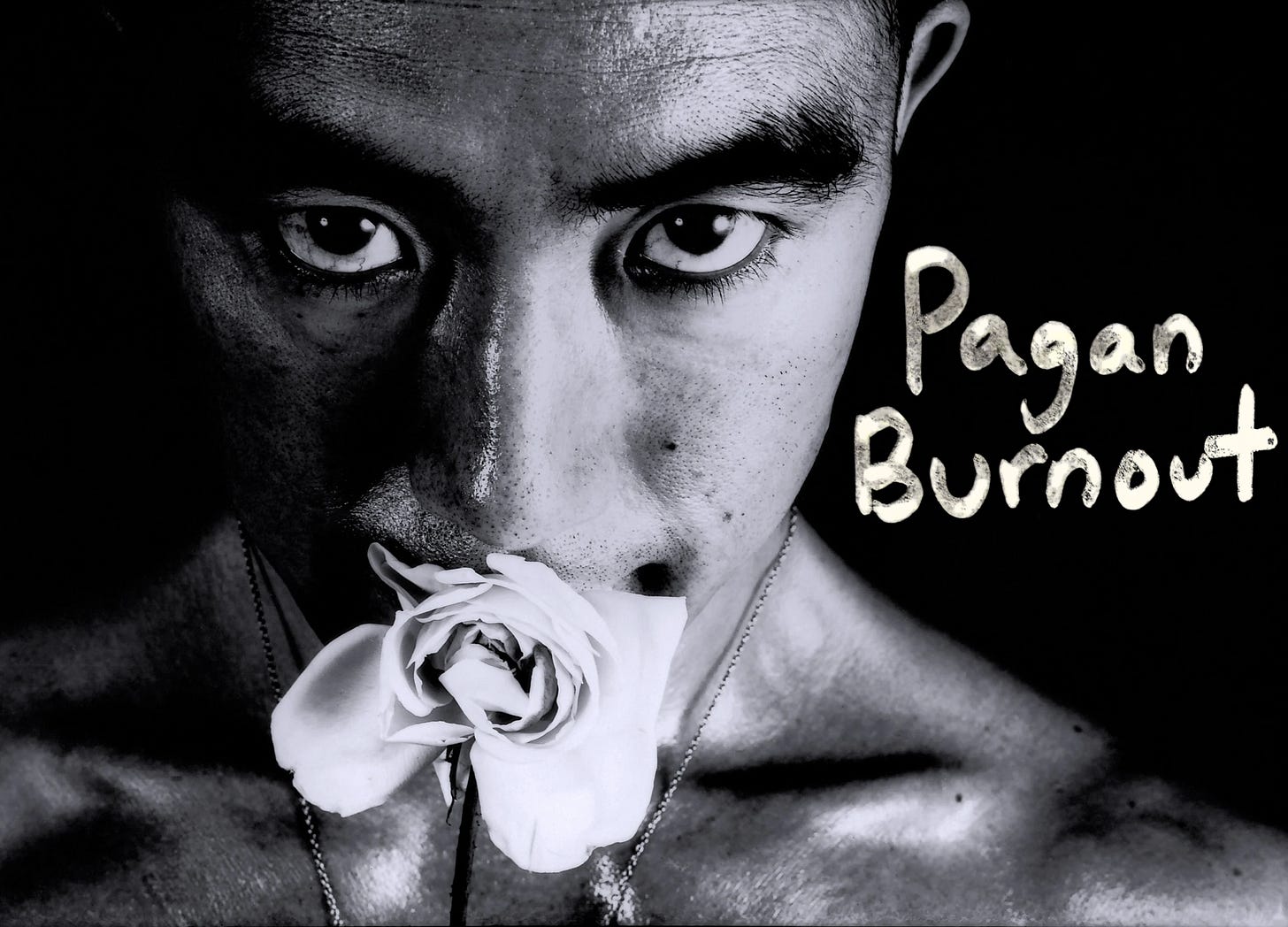

Pagan Burnout

When disorder becomes entertainment

ANNOUNCEMENT: Hello friends! I’ve decided to give this publication a small rebrand, changing its name from Catholic Politics to simply “Luca Adamo”, my own name. My recent work has turned out more personal and exploratory than I originally expected, and I don’t want to communicate a magisterial authority that I, a humble essay slinger, certainly do not possess. Now, onto this week’s piece!

I have a complicated relationship with pre-Christian literature. Whenever I read it, I am internally divided.

On one hand, I enjoy it as a literary matter for the little snacks it provides, like how in the Iliad the Greek troops are compared to “swarms of bees pouring out of a rocky hollow”, or how in the same poem Paris is compared to a horse whose “proud knees carry him swiftly”. Those moments are nice.

However, as nice as those moments are, I can never find myself enjoying pagan art for long. After a while I find that it loses its charm, and I, in turn, find myself growing bored and put off if I keep reading. As I’ve continued to grow in the Christian faith, these feelings have only become more pronounced. This is what I call pagan burnout.

Pagan literature didn’t always feel this way. I remember reading the Odyssey for the first time when I was in high school, and being completely engrossed. I remember the admiration I felt towards Odysseus for his wit and heroic daring. I remember the pangs of indignation I felt when Telemachus was dishonored by Penelope’s insufferable suitors. And I remember the cathartic relief I felt when he returned home to set things right and humble those nasty suitors. When I find myself reading the Odyssey now, these formerly exciting moments almost give me a headache to read – they induce pagan burnout.

I think pagan burnout is a product of the strain that comes from being of two minds. When I read ancient pagan literature, I don’t feel like I can fully enter into the world and mindset that the characters occupy, because that mindset is truly a foreign one. When I read the Odyssey today, having begun to integrate the Gospel with our emotions, I can see that “what is exalted among men is an abomination in the sight of God”, making the rotten emptiness that pagan “heroism” represents become crystal clear. When a work of art is empty at its core, all of its artistic adornment becomes nothing but an attempt to trick our soul into thinking it is beautiful, when it really isn’t.

Literature is only enjoyable when we can read it without holding back any part of our heart; Christians are able to taste the bitterness of pagan values through the sweetness of its literary brilliance, and having to consciously endure this bitterness makes reading these works exhausting. If you are a Christian and you do not taste this bitterness – if you experience unrestrained delight as Odysseus slaughters the suitors – your interior life is a joke, and you are bolted to the floor of Plato’s cave.

And speaking of Plato and other pagan philosophers, their work is only fruitful insofar as it serves as a handmaid to theology, whose object is the True God revealed to us in faith; faith which in turn is only ultimately fruitful (as far as our eternal end is concerned) insofar as it is perfected in charity. “For truly barren is secular philosophy, which is always in labor but never gives birth” (St. Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses).

I can already hear the Greco-Nietzschean screechers revving up their keyboards. I feel bad for them, that they do not experience pagan burnout. I think the little pagan within craves nothing more than to be thrashed by aesthetics – to writhe in pain under the crushing weight of the absurd, only to desperately find respite in the passing graze of ephemeral triumph or bliss. This is why Greek tragedy is so good, but why that catharsis we find so good about it doesn’t actually do us much good. Pagan burnout is the force which pries us from that fruitless dynamic to which the wounds of our nature cleave us.

If I wanted to be lazy I could end the essay right now by saying “erm, don’t worry chud! We can plunder the truths of pagan literature like the Israelites took the treasures of the Egyptians, and everything will be alright! The End!!!1! :D”

But I would never write that, because even though that is technically correct, it would also be boring and stupid. There is a whole entire side of pagan burnout that I haven’t discussed. Distinct from the false bliss of losing ourselves in disorder presenting itself as virtue is the trap oflosing ourselves in disorder presenting itself as disorder. I’ve found this trap to present itself more in modern literature, which tends to be more self-aware in a way that we can understand.

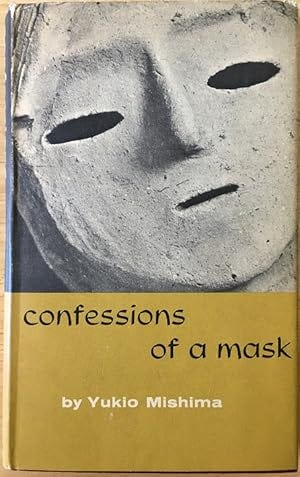

My favorite example of this honest disorder-as-entertainment comes from the work of Yukio Mishima, particularly his semi-autobiographical Confessions of a Mask. This book, told in the first-person, is a painfully detailed psychosexual study of the protagonist, whose violent homoerotic fantasies prevent him from loving properly, leading him to painfully sabotage his relationship with the beautiful pure-hearted girl who completely adores him.

The Greco-Nietzscheans I brought up earlier really like to romanticize Mishima’s writing, getting some kind of thrill out of his being a sensitive young pervert and his corresponding retreat into hypermasculinity. 99% of them don’t understand Mishima, only using him as an aesthetic vessel of troubled manliness which they use to peddle their elder-millennial “wat means” irony and stale quips about demographic collapse. The 1% who do understand paganism (i.e. Costin Alamariu) delivers insights of satanic genius, but these insights induce pagan burnout more than anything.

But going back to Mishima, I read Confessions of a Mask in one sitting on a 10-hour return flight from Rome, and as one could expect, experienced pagan burnout. However, as I said before, this time the exhausting temptation was not that of losing myself in the character’s false bliss, but was rather of losing myself in the character’s solipsistic self-reflection, itself reflecting its own kind of despair-fueled, self-gratifying consolation. Mishima spends the entire novel wasting his genius incurvatus in se, and invites us to join him in his self-imposed misery and do the same. But I don’t want to do the same! But I have to read the book. Hence, pagan burnout.

I even think good Christian books can be read incorrectly. Take Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina for example. Christian literature read without holding back our hearts and (most crucially) with Christian spiritual ends in mind, is a source of true edification. We, through mimesis, share in the characters’ joy and in their sorrow such that we don’t find ourselves incurvatus in se. But if one reads Anna Karenina to romanticize Anna’s sin, spiritually gooning alongside her throughout her affair with Vronsky; or uses Levin’s tendency towards solipsism as a breeding ground for our own, then the book is wasted.

For the Gospel-integrated heart, Anna Karenina is less conducive to pagan burnout than most books, because its Christian moral pervades the whole thing – but we still have to exert a little bit of vigilance, which I guess, in select moments of the book, means feeling a little bit of pagan burnout is appropriate. After all, Anna Karenina isn’t the Gospel.

Anybody who wants to do anything scholarly needs to read widely, because you’ll run out of things to say if you don’t. This wide reading will almost certainly include Homer and some stuff that is even worse, like Hesiod or Ovid. Maybe it will also include Mishima. But this calling to spend hours and hours reading pagan literature is the scholar’s burden, not his delight; he must suffer pagan burnout for the sake of the flock.

The burden is only made light in Christ, either by offering up the pagan burnout to Him or using it to engage in loving instruction. But the reading itself shouldn’t be leisurely; if you unwind after a long day by cracking open Confessions of a Mask, you need to be locked up and looked at – or at least looked at.

Thank you for reading my Substack! You can follow me on X @lucacadamo.

What exactly is the 'Christian moral' in the Anna Karenina book? I've seen adulterers be portrayed as unironic protagonists by non-Christians despite said failure being an important--even essential part of their character.

Excellent article. One question, how would you view the the writings of the divine comedy in view of pagan burnout?